To dream of a farmer is a sign that hard work awaits you soon, work that will require great patience from you.

(From Felomena’s dream book)

On one of the summer days when the inhabitants of Emilia-Romagna were already preparing for the peach harvest, the farmer Enzo Fiore heard the cooing of a turtle-dove — tor-tor. That bird, with its scaly pattern on the neck, was perched on the top of the magnolia tree growing opposite Enzo’s house and sang tirelessly, or rather cooed — low and muffled. The farmer thought: “A guest is coming.” Many years ago, when Enzo was about five years old, his mother told him that the turtle-dove came from the south, from Calabria, and brought heat on its wings. But his own experience suggested to the farmer another omen: that turtle-dove brought guests to the estate.

But right now the farm needed not a guest, but a worker. Enzo began thinking about it almost immediately after building the new two-story house. His father, Boscòlo Fiore, remained living in the old house, aged quickly, and became of little use in the peach orchard and vineyard. Enzo was not thinking of a partner, but of a young strong laborer, preferably a foreigner, to whom he could pay much less than eight euros per hour. And so, when the peaches began to ripen, Enzo realized he could wait no longer.

***

Denis Turov had long dreamed of moving to Western Europe. Of course, one could go on a tourist visa and disappear among the crowd of foreign workers. But, intending to settle abroad forever, he immediately ruled out the option of living as an illegal worker. While filling out his resume to send by email, Denis understood he had little to boast about: military service, three years of part-time study at a technical institute, and in parallel — work in electrical networks.

The resume in English and Italian was prepared for him by a former classmate polyglot, a student at Moscow University. Naturally, in the resume Turov exaggerated a bit regarding his professional qualities as a high-voltage electrician, but it was precisely this supposed high professionalism that interested the HR manager of a furniture company in northern Italy. One could say that only by a fortunate coincidence did Turov end up in that Italian factory, where he was signed to a one-year contract.

The Russian certificate for work on high-voltage installations was not recognized by the Italians, so Denis worked as a furniture assembler and, when needed by the boss, also as an electrician.

After a year the contract was not renewed, and Denis felt deceived by a cunning employer and almost offended by fate. He had worked diligently, never skipped, and at twenty-four it was certainly not an age to be fired. But a girl from Ryazan who worked as a manager in the factory told him that unemployment was rising and foreigners were the first to be let go. It was from her office computer that Turov found the ad from the farmer Enzo Fiore. In agricultural buildings there were constant problems with electrical installations and equipment, and Enzo was looking for a worker with electrician experience.

Turov arrived in Faenza in July. When he first saw Enzo — tanned, well-proportioned — he thought: “He looks like a former athlete.” Like many in that hot period, Enzo wore a white T-shirt and short beige shorts. On his feet — open sandals. Chin unshaven for a long time, black beard ready to grow thick. Receding hairline, gray at the temples: the farmer was at least forty, but clearly in excellent physical shape and resembled a soccer coach. In his whole figure there was confidence and philosophical calm.

They drove out of the city in Enzo’s jeep and sped between vineyards and cornfields. On the way to his estate Enzo Fiore uttered only one sentence:

– Last month it rained only once.

The new white two-story house of the Fiore family stood in the middle of the Po Valley, almost like steppe, under a cloudless sky and scorching sun. The sea was half an hour away, but as it turned out, Enzo never had time to go there.

Denis mentally classified the new Fiore house as a cottage: it certainly did not reach the size of a villa of new Russian rich. No high fences with automatic gates. But the facade was very graceful. The entrance consisted of square brick columns topped with a tiled roof that looked like an exotic cap. This sort of open colonnaded veranda ran almost the entire length of the facade, creating saving shade. On the second floor there was an unglazed loggia from which one could see the fields and low mountains shimmering in the distance in the heat.

The owner immediately took Turov to see the estate and agricultural lands. In a year of factory work Denis had learned some Italian and understood almost everything the farmer said.

First Enzo showed him the working yard, sheds, agricultural machinery, isolated fruit trees. On the pomegranate tree large fruits already hung. When Enzo called the persimmon tree “Romagna persimmons” and in Latin Diospyros kaki (“fruit of the gods”), Denis thought: “I’ve found a cultured man.”

– Persimmons are eaten in November, Enzo explained. After lunch and only when ripe.

Then they walked along the vineyard where two varieties grew: the green one and the small dark purplish one that smelled of wine. From the vineyard they turned into the peach orchard, which seemed immense to Denis. The trees stretched in orderly rows toward the mountains.

Turov asked:

– Are there other workers?

– Me and my wife, Enzo replied and smiled. The smile seemed kind, but Denis understood that the farmer saved on labor and therefore an unexpectedly wide front of work awaited the Russian electrician. In such cases Turov was accustomed to mentally repeat to himself: “A man can do only what his strength allows. Perhaps a little more.” Turov did not fear work, and anyway he had nowhere to retreat. In Russia no one waited for him: his parents were dead, and in their two-room apartment in Lotochino lived his older brother with wife and daughter.

Between the rows of peach trees there reigned suffocating heat, the air was saturated with the aroma of ripe fruit. The branches fanned out overhead, supported by iron wires that Enzo had stretched between the poles along the rows. Underfoot lay many fallen peaches, beautiful, juicy, but a true farmer does not eat fallen ones and does not offer them to guests. What has fallen is lost. Enzo chose a fruit from the branch for a long time. He took one, looked at it from all sides and threw it away. He looked for a better one. Finally he chose one and handed it to Denis. The skin was smooth and Denis finally realized it was a nectarine. Enzo confirmed: “nettarina.” Despite the rosy appearance, the yellowish flesh was still firm, but sweet to the taste.

On the way back Denis also saw the vegetable garden where watermelons, pumpkins and tomatoes were ripening.

– Nice orchard, said Denis, trying to express with his whole person and intonation respect for the hardworking owner. – So many peaches.

Enzo nodded and invited the worker to lunch.

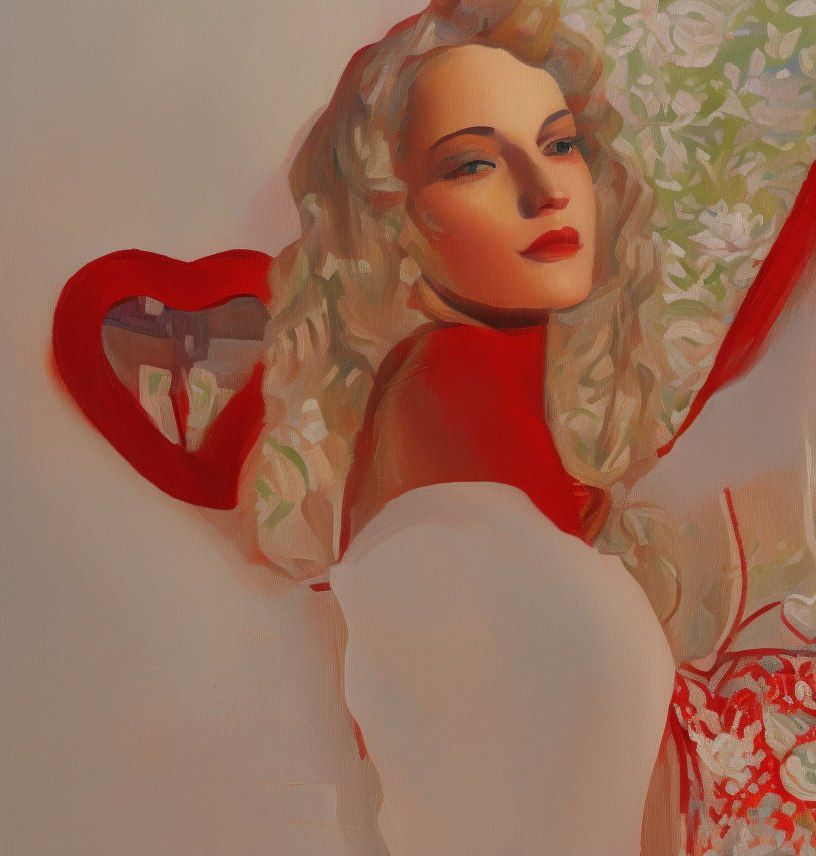

The table was set by a young woman dressed in wide white trousers and a loose light-blue blouse with a deep neckline. Neck and arms were covered with uniform, not too dark tan.

– My wife Anna, Enzo introduced her, and ardent sparks flashed in his brown eyes. That is how confident Don Juans sometimes look when they know that in a minute another rare piece will enter their collection.

Denis immediately decided that Anna was not quite a typical Italian. Rectangular face, high forehead, elongated chin, large wide-set eyes. Broad cheeks, and the left cheek seemed larger than the right. “She probably contours the chin and forehead with blush,” he thought, and mentally added that makeup did not suit her much. In photos she probably looked worse than in life: it always happens with irregular features. Anna was not a beauty, but attractive, and her eyes and long dyed light chestnut hair could make a strong impression on a man.

Everything on the table was home-produced: fruit, pork, chicken. And naturally wine.

– Help yourself, Giovanolo, said Anna, pointing with a sad smile at the pork dish.

“They called him Giovanolo,” thought the Russian looking at the pieces of pork. “It seems here they don’t eat someone they don’t know!”

At lunch Denis discovered that in her culinary preferences Anna sometimes combined incompatible things: for example, on orange melon cubes she put smoked meat. However, that unusual canapé pleased Turov very much.

When Anna placed the dessert bowls, she looked straight into Denis’s eyes from behind a wavy chestnut curl and smiled. That bold smile, the movement of her breast as she leaned over, the chocolate aroma emanating from her body — all this enchanted Turov. “Where did she get such a perfume?!” It was as if a wave of young energy had hit him. The dessert made with nectarine, walnuts and kiwi completed the effect.

Catching the farmer’s glance, Denis noticed with horror that there was understanding in Enzo’s eyes and at the corners of his mouth. But a moment later Enzo’s face, eating the dessert, became perfectly serene again.

Turov continued to feel Anna’s curious and probing gaze upon him. As if she were analyzing him in his masculine capacities: both working and otherwise. This kept unsettling him until the homemade wine relaxed him.

They gave him a room in the old house, which stood about thirty meters from the new one. In his room there was a window and behind it large pomegranate fruits were ripening. This pleased Turov very much, because the pomegranate tree hid part of the peeling wall of the opposite shed.

That day Turov felt like a guest in the Fiore estate. But already the next morning everything returned to its place.

Enzo woke him at six, they drank coffee together and went to the orchard. There the farmer gave a detailed briefing on the work to be done.

Turov listened attentively. From Enzo’s explanations he understood that peaches do not ripen all at once, so they have to be picked selectively for almost a month and a half. The fruits are removed carefully, trying not to bruise or crush them. Only those almost fully ripe but still firm are taken from the branches. Neither the peaches whose skin is not yet red nor those too ripe, because they rot quickly and are not suitable for transport.

During picking Enzo used a motorized platform. On that platform, which could rise up to two meters and move on wheels along the tree rows, there were crates and boxes for fruit. That is where the pickers stood: Enzo, Anna and Denis. They detached the nectarines from the branches and gently placed them in the crates, in individual compartments. Anna, however, was mainly occupied with sticking labels on every peach. At the same time culling took place: damaged fruit went into a separate box.

Denis now knew that fruit saturated with sun heat, ripe and fragrant, had to be delivered to the agricultural consortium within twelve hours, otherwise without refrigeration they would begin to deteriorate. At the consortium there were special cold rooms and the council took care of everything: storage, transportation and sale of the harvest. But the farmer was left with only seven cents per kilo for good fruit, and even that not immediately, but as the goods were sold.

– And what do they do with the fallen peaches? Denis asked.

– We’ll pick them up later, Anna answered, looking at Turov with narrowed eyes from under the headscarf hiding her beautiful hair. And she frowned. – For those they give only three cents per kilo.

“But in the shops nectarines cost two and a half euros per kilo. It’s pure robbery!” thought Turov.

– Before, the Fiore used to take peaches to Ravenna, Anna said. And sold them at the market.

But those happy times, as Denis understood, were long gone, together with the lire and national leaders. Now the markets were controlled by monopolies that had no need for small farmers and their goods.

Enzo seemed not to hear his wife’s words. He was completely absorbed in the work, which apparently did not tire him at all. The farmer looked at the peaches with kind brown eyes and smiled faintly. His hands worked quickly and surely among the branches, detaching the fruit. He had very strong hands, covered with black hair, with tenacious fingers. Those hands were the true treasure of the farmer, because the speed of picking determined the amount of marketable fruit.

During short breaks he smoked in silence, lost in some thought, but not worried, rather dreamy, as if mentally he was on an island lost in the ocean. Probably only with such philosophical calm in the soul could one work with three people, without hiring laborers, twelve hectares planted with peach trees, vineyards and pear trees.

Anna, on the contrary, talked incessantly. For example about the father-in-law, a great worker who “always” worked. Now old Boscòlo Fiore had aged and only left the house to walk in the yard, from the shed to the vegetable garden and back.

August came, no less hot, and there were still countless peaches on the trees. To distract himself mentally from work, Denis imagined himself as an agrotourist. Tired of city chaos, office air conditioners and exhaust fumes, he would feel the need for natural products and physical labor in nature. For a while these thoughts amused him. But they completely disappeared when he returned home after work and felt pain in his back and legs.

And then it turned out he also had to look after Boscòlo. At lunch Turov cooked ravioli for himself and the old man, poured them into plates with broth and grated real Parmesan on top — strictly the genuine one, with the label showing the peasant with the plow pulled by two oxen.

Sometimes, very early in the morning when the Moon was still in the sky, tall thin Boscòlo made several rounds in the yard, and if you watched him you could notice the approach of infinity and the cosmic completeness of the old man’s path.

Boscòlo’s morning walks became shorter and shorter, and by autumn he only did them arm in arm with Turov. The old man liked to tend the tomatoes and dragged Denis to the vegetable garden. Now Turov had to take care of that garden too. Fortunately, the boar Giovanolo, eaten in July, had been the last inhabitant of the pigsty, otherwise Turov would inevitably have become a swineherd as well.

The saying that a man can do only what his strength allows quickly lost its meaning. Turov was gradually becoming farmer, mechanic-worker and caregiver at the same time. And with the five hundred euros Enzo gave him every month — ridiculous money for Italy — there was no saving. Of course, he paid no rent, so the money was only for food and clothes. And in the countryside expensive clothing was certainly not needed.

If one put a big cross over the future, then nothing was needed at all: no car, no nice clothes, no own apartment. But the thought that he had left Russia for the Fiore and their peaches now filled him with rage.

Enzo had promised Turov a bonus of fifteen hundred euros after the complete harvest. But now the farmer said he would pay it only if Denis continued to take care of his father. Naturally, once that money was earned, one could look for another job. Or return to Lotochino and resume work in the electrical networks, which were unlikely to go bankrupt in the next hundred years.

Such thoughts somewhat calmed Denis, gave some meaning to life. And watching the Fiore family he began to respect them for their enormous labor. And even to pity them.

On Saturday evenings Enzo grilled meat and eggplants on the barbecue. He roasted pork, chicken and sausages until they were crispy, convinced that even overcooked meat on live fire could not harm the body. Especially when accompanied by wine and slightly carbonated “mineral water.” During those short evenings Denis again tried to imagine himself as a tourist or even a 19th-century Russian nobleman who had come “to the waters.” But it didn’t work.

In the evening the village — if one could call that scattered set of estates among the fields — was almost dark, and to Turov it seemed he was on the outskirts of Lotochino district. Then he asked Enzo or Anna for permission to sit in the living room at the computer to chat on Skype with his brother.

While he was at the computer, a somewhat strange life in the details of this alien family flowed around him. He heard Anna, who was cooking in the kitchen, constantly muttering to herself, monotonously and incessantly, almost as if she were delirious. Once, listening carefully to Anna’s murmur, Turov discovered that doctors had long ago given her their verdict: she would never have children of her own. Why? Anna thought it was the fault of the grandfather who after the war had used too many chemicals in the corn field. And not only him, but all the neighbors. That’s why there were so many childless couples around.

At certain hours, according to the timer, a white disc-shaped robot vacuum cleaner named Filipino came out of the small pantry and industriously began circling the large living room, collecting the dust that incredibly quickly accumulated on the tiles, forming rolling dust bunnies.

After the grape harvest the Fiore couple calculated the income from the sale of the entire crop. For the first time in three months of farm life Denis saw Enzo gloomy, eyes dull. From an overheard conversation he understood that the sale of fruit had brought in only six thousand euros.

– Why don’t you talk to your cousin? Anna reproached her husband. He has connections, he does business in Ravenna.

– I called him, Enzo answered in a dull voice.

– And what did he say?

– He said: “Why should I buy your peaches! Better sell me the whole estate.”

– That’s what your cousin said?

– Yes.

Then came Anna’s lamentations and, for the first time from Enzo’s lips, a string of untranslatable curses.

Enzo paid the worker nine hundred euros for the picking work, and promised to pay the remaining six hundred in installments with the monthly salary.

Autumn came. In autumn they pruned the branches in the peach orchard. Overly dense crowns weaken fruit production and trees age quickly. That is why peach grower Enzo regulated fruiting and lighting inside the crown with skillful pruning of branches and vertical shoots.

The pomegranate tree behind the window of Turov’s room lost its yellowed dull leaves, and the reddish-brown fruits hung like Christmas decorations. In the morning Denis liked to stand for a few minutes with his coffee cup at the window, admiring the heavy pomegranates and imagining them as planets that had arrived on Earth from a distant warm galaxy.

Then the pomegranates were picked, put in boxes and hidden in the shed, and the world outside Turov’s window lost color. And after picking the persimmons, winter arrived.

One winter evening, having left the grandfather watching television, Denis went to the main house, to Enzo. In the large living room warmed by the fireplace one could stay at the computer until late. Enzo was already resting there: after dinner he had lain on the sofa in front of the fireplace, smoked a cigarette, leafed through the newspaper “Ravenna”, found an article about football and… dozed off as usual. On the square glass coffee table beside the sofa stood a glass and an empty bottle of aperitif. At that moment Enzo’s face seemed to Denis puffy, resembling Mussolini’s face, even though Fiore had never been a compact boar like the late Duce.

In winter, when under Christmas the fields in the morning were covered with white fog and then it began to rain, even in the sound of rain in the yard Denis heard Anna’s voice: the same dull methodical muttering or incomprehensible moaning.

Usually around eleven Anna came into the living room and woke her husband so he would go upstairs to sleep in the marital bedroom.

This time it was the disc vacuum cleaner coming out from its corner under the stairs that pulled Enzo out of his drowsiness.

– Filipino shouldn’t be cleaning now, Enzo worried a little, but almost immediately calmed down: – Anna moved the timer… She does it so I don’t sleep here. Women, you know…

Denis already knew why Enzo called the vacuum cleaner Filipino: not long ago there had been a great many Filipino domestics and cleaners in Italy.

Looking at the object gliding over the tiles, Enzo, half-asleep, said:

– On the news they said yesterday the Filipinos ate a megamouth shark. The rarest in the world… Swallowed it whole. Give them the chance and they’ll eat everything. And our government always defends them.

– They say Filipinos are excellent sailors, Denis tried to say something.

– About sailors I don’t know. But you should have seen how polite our lawyer was with that Filipino cleaner! He even justified him for poor work…

Enzo was almost falling asleep again, but then he started and opened his eyes. Without blinking he stared at how Filipino continued cleaning the dust around Denis’s feet.

– What can we do, Enzo suddenly said. Who will all this go to? When I’m as old as my father, who will work in the orchard? Some Albanian?… Or a humble Filipino? A family man, good Catholic, with tight trousers, shirt out and a hat. With a pompous Spanish name: Carlos… Or Balthazar, what do you think?

– Maybe José? suggested Denis and immediately realized he had made a mistake: Enzo’s face twisted in pain.

– And they’ll say: here once lived Enzo and his wife, now it’s José. – The farmer, it seemed to Denis, looked at the vacuum cleaner with hatred. – And then they’ll completely forget Enzo, and only José will remain. Not very rich, but who loves children very much…

From the second floor Anna began to descend. She muttered something about her sleeping husband, about his passion for fertilizers… About strange Russians who have nothing better to do than ruin their eyes in the virtual world. She woke her husband and took him upstairs.

Already past midnight Anna came down again to the living room, in pajamas. She was not ashamed of Denis. Besides, the main light in the living room was off, and the room was only faintly lit by the dying fireplace.

– Denis, you said you were an electrician, Anna said and went into the small guest room. She brushed Filipino with her foot, and it suddenly started again.

– Yes, I worked, Denis answered.

– Come see the socket, Anna’s muffled voice came from the guest room.

– Now?!

With her anyway it was useless to argue: she could have a fit of hysterics. After all, she was only calling him to look, the repair could wait until tomorrow. And Denis followed her. And Filipino threw himself at his feet, as if not wanting to let him pass.

In the small room the lamp above the wide bed was on. Anna stood by the bed. She had already removed the top of her pajamas. Then she removed the rest. She sat on the bed, lay on her back, offering Denis the opportunity to look at her entirely.

Anna’s skin was white. Wide hips, on the large hemispheres of the breast tiny nipples that had never known a child’s greedy mouth. Anna had a rather narrow waist, something Denis had never noticed. Apparently all those shirts, blouses, loose dresses she chose precisely to hide the abundant breast. And she had hidden the main thing — with that there was no competition in her body — the waist, which can belong only to a woman capable of bearing healthy children.

– Well, why are you standing there like a post? Come here, Anna called.

Filipino darted between Denis’s legs into the room and set to work: went under the bed, then reappeared on the other side, turning and checking the floor centimeter by centimeter. Its industriousness was so out of place in the small room where a naked woman lay on the bed.

Anna, raising her head, propped herself on her elbow and she too looked at the vacuum cleaner — with great suspicion, slightly narrowing her eyes… In her body Denis noticed a certain irregularity. And he understood that he absolutely did not want to possess this woman, with those Rubens-like heavy hips so ill-suited to a waist. A kind of failed hentai drawing manual.

Anna, shaking herself, turned her pale face toward Denis, looked at him with wide, almost mad eyes, and ordered angrily:

– Come on!

Filipino, passing nearby, seemed to stumble: it stopped and winked at Denis with its little green eye.

Denis took off his shirt, then his jeans. He understood that if he did not obey, tomorrow Anna would say terrible things about him — until Enzo threw him out. Even the balanced Enzo would not endure another of her attacks of neurasthenia, headaches and irritability. A faint thought passed: “Enzo gave me shelter and work…”, but his legs carried him to the bed on their own.

The female body, scented with chocolate, was tense, it had more energy than biology and anatomy, and Anna knew how to use it, how to control Enzo and Denis with that energy, even Filipino. How to dominate that bed, that room, that abandoned house in the hard arid Po plain that sank a little deeper every year waiting for the sea high tide. The male brain was powerless before that energy…

The next morning Enzo went to work as a day laborer for a rich farmer. At first he went alone, then began taking Denis too. They worked eight euros an hour as loaders and tractor drivers. They got up at five, drank coffee, took food in plastic Tupperware containers and left in Enzo’s car for fifty kilometers from Faenza. They returned home only at eight in the evening. Although Enzo kept all the earnings, Turov felt pangs of conscience. He felt like a traitor, a Judas, and dreamed of leaving those places as soon as possible.

Meanwhile Anna was raising rabbits. She had managed to come to an agreement with the owner of a trattoria where rabbit dishes were very much in demand and expensive.

At Christmas Enzo and Anna left the estate to Denis and went to relatives in Verona. Two days Turov spent alone, not counting the almost senile old Boscòlo, whom he had to feed with a spoon, wash, dress and walk.

When Enzo and Anna returned, Denis, exhausted by hunger for human contact, asked permission to go for a walk in Bologna or Mantua.

– No problem, even tomorrow, said Enzo, whose face clearly showed how happy he was to be back from relatives in his own estate. That evening the Fiore couple left Denis alone on the ground floor at the computer, and went up to their room. And almost immediately passionate sighs and the muffled creaking of the bed reached Turov. Enzo had not even bothered to close the bedroom door properly.

“For them I’m a piece of furniture!” thought Turov turning off the computer. “Or a soulless robot.” — Denis stood up and angrily kicked Filipino passing by. He hurried out toward the old house.

The next morning the farmer took his worker to Faenza. Enzo was in excellent mood. He turned on the radio, listened to English songs and even tried to sing, although he had big problems with English.

– In Mantua find yourself a girl, he suddenly advised Denis. There are plenty there.

– Sure.

During the whole trip Turov could not wait for Enzo to disappear from his sight together with the jeep.

Turov set off on a trip to Bologna, where he had already been before, and then to Mantua.

In Mantua it was cold and damp, despite nine degrees above zero. A thin unpleasant drizzle was falling, and the few passers-by, covered with hoods of jackets or huge umbrellas, hurried toward the typical Italian arcades, disappearing into shops and pastry shops where in such weather it was nice to drink hot chocolate. The café-chantant umbrellas were closed, and plastic chairs were stacked one on top of the other — like curved green columns.

Having reached the historic part of the city, Denis saw an Afro-Italian selling various objects from a stall all at the same price — five euros. Denis bought a large green umbrella and headed to the Palazzo Ducale museum. But in the galleries and corridors of the Palazzo Ducale it was as cold as in a cellar. After visiting two or three of the five hundred rooms of the Palace, Denis thought: “At the entrance they should give fur hats with earflaps!”

After the palace, imprisoned by the medieval cold of the dungeons, the streets of Mantua seemed warm and familiar to Denis, and without noticing he almost reached the river bank, ending up in a deserted park, at the end of which stood a monument. A bronze man, majestic as an emperor, dressed in a toga, arm bent at the elbow, held out his palm under the weeping skies. Denis did not reach the monument because the rain intensified and reddish, almost gravel paths began to form puddles.

To amuse himself a bit he bought a Miliardario lottery ticket in a tobacconist. Without going outside, he took out of his wallet a fifty-cent coin with the image of the offshore zone of San Marino. He always carried that coin in his wallet, hoping that one day it would bring him luck.

“Better if I had gone to Parma,” thought Denis, scratching the lottery ticket film with the coin. “There, in the National Gallery, apparently there’s a fantastic painting exhibition.” Here he felt his heart beating irregularly. All ten digits indicated a prize of 10 euros. He looked at the ticket again and again, and convinced himself: he had won one hundred euros. It was luck!

Now he had something to do: cash the ticket and celebrate the win in a café or restaurant. So when the tobacconist asked: “Do you want more tickets?”, Denis confidently answered: “Soldi.”

For a while he walked, looking for a pleasant place to spend time. And here, in the historic part of the city, he liked a literary café — a literary café named “Venezia.” He passed through the bar into a wide arch, behind which was a very cozy room with white walls on which black-and-white photographs in square frames were hung, and narrow cabinets with a collection of teapots, cups and gift plates.

Denis took off his jacket and hung it on the wide, shell-like back of a wicker chair, sat down and looked around. Half the tables were empty, and in a corner under a Russian samovar standing on a shelf attached to the wall, a group of elderly Italian women were animatedly discussing something. No, they were simply commenting in their usual way on the sales discounts. Sales, sconti, saldi, shopping — what else could women talk about in the days before New Year!

They did not look like poetesses, but a distinguished gray-haired gentleman standing near the bookcase and diligently searching for something in one of the color-illustrated volumes could be a writer or art critic.

Music was heard, a waltz. The man took a Siemens from his crossbody bag, brought it to his ear and said in Russian:

– You already wished me Happy New Year! Party animal, call me in a week. I’m abroad, — and he put the phone back in his pocket.

Watching his compatriot, Denis realized he had chosen the most comfortable spot in the café, in the little corner by the literature cabinet. Near his table, next to the coat rack that looked like a pair of skis taped together, on one of the free chairs lay a short woolen coat and a white scarf.

When the waitress brought the gentleman the menu and wine list and left, Denis approached the bookcase and quietly asked in Russian:

– Excuse me, do you know to whom the monument in the park is dedicated?

– In the park? the man repeated somewhat confusedly and looked at who had addressed him. Denis immediately noticed that the gentleman’s German titanium eyeglass frames cost no less than a hundred euros.

Denis raised his right hand, imitating the sculpture. The man answered with a smile:

– To Virgil. They call him the Swan of Mantua.

– Are you a writer?

– No. But, like Onegin in Pushkin, I once remembered “not without sin two verses from the Aeneid”… Excuse my curiosity: are you also a tourist?

– I work here. Allow me to introduce myself. Denis. Would you like to sit at my table?

– I already ordered. So better you at mine. It’s very cozy here, in the corner. And explain to me what mascarpone is. Because I ordered I don’t know what.

When Denis sat down at the Russian’s table, he introduced himself:

– Gursky, Evgeny Borisovich. I’m in publishing. I came to see if I should move here forever. I would like a quiet old age in a cozy environment. As Aristophanes said: “Ubi bene ibi patria” — where it is good, there is the fatherland. Here, let’s admit, it is comfortable.

– And in Russia life is not comfortable?

– It depends for whom…

The waitress brought white wine and risotto “con puntel” — rice with fried meat. And the mascarpone Gursky had ordered earlier. The men toasted their acquaintance and began eating the risotto.

– Mascarpone is a cheese. It looks like cream, you can spread it on bread, Denis explained. It’s made from buffalo cream.

Gursky tasted the mascarpone, smacked his lips and with facial expression showed that the taste of the product was excellent.

– Any Romeo here would definitely gain weight and forget about Juliet.

– Excellent desserts are made with it, Denis said, politely hinting that mascarpone is eaten at the end of the meal. – You say it’s comfortable here. It depends on the point of view. I lived here for a couple of years… In Russia it’s better.

– Really? asked Gursky, devouring the risotto with appetite. – Allow me not to believe you.

– You may not believe. First impressions fade quickly. And people become dull. At first one goes into ecstasy over local aromas, like a young lady. Ah, what a wonder Italian bread is! Fragrant, different shapes, there’s even one in the shape of a starfish. And what about salad with figs and ham!.. It went well for me: I settled with a farmer, Enzo. We worked from dawn to dusk. And in the evening — no comfort: dinner and to bed. Whereas in Russia comfort still means a job you like, even if the pay is low. Vacations — with camels in Egypt or with poachers on the Akhtuba.

– So that’s how you understand comfort, — Gursky tried to smile.

– And so? A decent jacket that doesn’t get dirty, and most importantly cheap, like in Italy! Old people have pensions… well, at least one. Friday home in a hurry. TV — like a live thriller. On the sofa — the cat or, in a cage, the guinea pig. The dacha — to work there and not only. Weekend, shashlik by the river, friends.

– It’s been a long time since you returned to Russia, Gursky noted. He pushed away the plate with the leftover risotto. – In Moscow wherever you go, whoever you ask — everyone has problems. Crisis. As we say: surplus personnel in conditions of very low wages. And Enzo probably prospers.

– He went bankrupt. That’s why he cleans shit on someone else’s farm, eight euros an hour. Together with passing Albanians. — Turov did not speak about his day trips with Enzo.

– You see, young man. Everything we see today is the result of the so-called global economy. And Russia is also to blame.

– And what does poor Russia have to do with it?

– How many people came here from all countries and villages. Just count the women! I heard that in this province alone there are seven thousand Ukrainians.

– Women are not peaches, Turov noted.

– True. But among them there are energetic ones in abundance. And then they brought their men here — work for everyone! Former kolkhoz chairmen bought peaches in China, sell them in Italy, and take the capital to Russia. Here you have “Wimm-Bill-Dann”, and Parmalat. And the port of Rimini that Vitya Vekselberg bought. Can the production of the small farmer Enzo withstand such competition? Politics, my friend, is involved, there’s no escape…

For a while Gursky was silent, waiting for the interlocutor to say something. Then he added:

– If it’s unbearable for you here, go to America instead. Many of ours work in commerce there.

Denis, who chatted online with emigrants from various countries, smiled and began to tell:

– A girl in the United States worked as a cashier in a supermarket. There it’s normal in the evening to put money in a box covered with adhesive plastic, and no one counts the dollars at the end of the day. And early in the morning, before the shift, another cashier comes, checks and writes a note about shortages. For my acquaintance it was a nightmare. It lasted only six months, then she quit. And she got a job in a clothing store. There, apparently, the system is excellent. Late in the evening after closing, a report of all transactions is printed — credit cards, receipts and cash. You count, enter the number of cents, dollars, ten, twenty bills and so on, then a new report is printed which serves for balance comparison. In the presence of the manager and, naturally, with computer-generated reports. It seems like a dream! But not quite. As it turned out, the management practiced rotating cashiers, that is, changing four or five a day behind the register. And then you tremble like a leaf, counting on the honesty of colleagues. In short, another abyss.

Denis had not talked to anyone about these topics for a long time, so, seeing an attentive listener in Gursky, he talked and talked, and could not stop:

– And American salespeople have few vacations. You have to work five years in a company to earn three weeks of vacation, otherwise only two. During vacation they pay only for five days. Sick leave usually — seven days a year. If you don’t use them, they disappear. They are paid like vacation: a little less than a full week’s salary. Health insurance is expensive, but covers ninety percent of medical costs. Without insurance — it can’t get worse: a crown without insurance — a thousand dollars down the drain!

– In Moscow even with insurance you pay a thousand for a crown, Gursky became animated. – But… we are in a literary café, and we talk about money. Not good. Too bad the muse didn’t descend here. I would have composed a fairy tale.

– About what?

– About contemporary Russia, of course. And the fairy tale would begin like this: “Once upon a time in the dark forest there lived Friske, Deripaska and Pisanka*…” (*TV presenter, publisher, actress known at the time)

Both burst out laughing. Then they raised their glasses and clinked them, attracting the attention of other customers. Drinking wine from the glass, Denis asked:

– Wouldn’t it turn out too glamorous?

– No, what are you saying! Glamour is the vulgar’s idea of luxurious life… Excuse the indiscreet question: do you, Denis, go to church?

– Of course, I go… Rarely. Recently the Orthodox community was given a Catholic church building.

– Perhaps it’s good that it’s rarely.

– Why?

Gursky did not answer immediately.

– I cannot answer this question briefly. In this case brevity is the sister of the tarantula! — Gursky laughed at his own pun. – Let’s talk about something else for now. You need money, right? And I need a smart assistant who knows Italian. I propose a kind of partnership. You will help me buy an inexpensive little house in the village. Arrange with Enzo for three days off. I’ll rent a car. Say, two hundred euros suit you?

– Four hundred.

– Let’s settle on three hundred.

Denis thought a little:

– Plus food, he specified. – And keep in mind: no Russian emigrant likes Italian cuisine. With Enzo and his barbecue it went well for me.

When Denis returned to the village and asked Fiore to let him go for three days, Enzo reacted to his worker’s request with displeasure and unexpected distrust. He tried to find out if the worker had fallen in love with some Ukrainian woman. Turov tried to tell about Gursky, but saw that Enzo did not believe a single word.

– We have a lot of work, Enzo said frowning, and categorically refused Denis’s request.

Having learned from the phone call that Denis could not help him in any way, Gursky became sad, but immediately calmed down and said:

– You, Denis, should still get an education. No matter where, in Russia or Italy, but you must study. My advice — enroll in university. Try your luck! As they say, if you don’t bite the nut, don’t complain about poverty.

The next morning, when Turov returned to his room after the shower wrapped in a towel, he saw Anna. In underwear — she had occupied his bed. And she was sitting in a very free pose — one leg bent under the other, so that her knees were wide apart. Seeing Denis, Anna stood up, approached him and embraced him. Her warm body, soft skin — everything smelled of grapes. Those changeable scents of hers literally drove Turov mad. He asked:

– What perfume is that?

– Do you like it?

– Very much.

– Creams from San Marino.

Greedily he possessed Anna, without even thinking that the old man in the next room had surely woken up.

…When he got up from the bed and began to dress hurriedly, he found on the table the risotto, rolls and meat prepared the day before on the barbecue.

– This is for you and Boscòlo for lunch, Anna explained, raised her arms and stretched on the bed like a satiated cat. Then, as if half-asleep, she murmured with a smile: – Even noble causes have a price.

– Noble? Turov clarified, somewhat perplexed.

– It just came to mind…, she stood up and, without haste, began to dress.

– Interesting, what?

– How I wanted to take a child from the orphanage. First from the Italian one, then I got in touch via Internet with Ukraine. But it turned out that even noble causes have a price… Imagine, Enzo learned the amount and says: “You made a mistake, you called a jeweler. A newborn cannot be made of 750-carat gold,” — to Denis it seemed that the last words she said with hissing rage. – Or maybe it’s not the fault of the chemist grandfather. Maybe it’s Enzo’s fault. What do you think?…

At that moment a strong old man’s cough was heard, and the door swung open. In the room, straight at the half-naked Anna, stood Boscòlo looking.

Turov took cigarettes from the nightstand and, turning to the window, lit one, waiting for Anna to leave the room and the terrible situation to resolve itself.

From the window he saw Anna hurriedly cross the yard and disappear into the new house. Behind her, leaning heavily on his cane, old Boscòlo shuffled. What they talked about afterward in the house was easy to guess.

All day Denis waited for Enzo to come to him with a gun, or call him for a showdown. But Enzo called him to work in the garden. And again they pruned branches. The two of them. In silence. Denis deliberately worked so that the farmer was always in his field of vision. “All that was missing was for him to stick the pruning shears in my liver,” thought Turov.

A week passed, another. No one said a bad word to Denis. Anna no longer came to his room. By mid-February Boscòlo became completely ill, hardly got out of bed and walked to the toilet along the wall, to which Denis had deliberately screwed handles.

One evening Turov, after feeding the old man with a spoon, went out into the yard and saw Enzo standing in front of the house with a bottle of beer and looking at the stars that had appeared above the peach orchard plunged in darkness. It was unusual for an Italian — to drink beer outdoors in winter.

Hearing the worker’s steps, Enzo, without turning his head, asked:

– Have you ever seen peach trees in bloom?

– No.

Denis stood beside the farmer and also looked at the sky. Low on the horizon shone a bluish star.

Enzo took a sip of beer and, still without looking at his interlocutor, said:

– Too bad. It’s time for you to leave.

Turov looked at the star for a while, which seemed familiar to Denis… Yes, yes, he had seen a similar one as a child, in his native Lotochino. Once until midnight he looked at the stars from the window, because that day was Denis’s birthday, and his father had given him a small telescope. His father had also said: “If you travel, it will help you not to lose sight of home.”

– Farewell, Enzo of Faenza. — Denis felt anger again.

– Not now, the farmer’s voice trembled, or only seemed to Denis? — Tomorrow morning you’ll get the full settlement. Complete, no deductions. — There was not a trace of emotion in Enzo’s voice.

Denis looked through the illuminated living-room window and saw Anna, dressed in a very loose dress. The mistress stood in front of the mirror and for some reason thrust forward and stroked her belly. At her feet the vacuum cleaner traced witch circles.

Denis Turov was seized by a shiver, then by heat. The strong desire to grab the farmer by the throat he barely managed to suppress with great effort.

– We are all here… Filipinos! — he muttered, addressing the bluish star.

Then, on stiffened legs, he headed toward the old house. It was time to prepare for departure.

***

When there is no rain and the usual thick fog of early January, the New Year dawns of northern Italy are fresh and transparent. In the humid air, heavy for a Russian, hangs a nearly full clear moon. The low mountains, which in the evening softly blend into the yellowish horizon, in the morning sharply outline themselves against a tender pink sky background. In the farmsteads scattered among fields and orchards of the province, in that part called Romagna, perfect silence reigns.

At eight in the morning the bells suddenly strike on the square of the nearest town, and that sound, delicate, as if the clocks fear not only waking people who will get angry and file a complaint with the police, but also offending nature. But the farmers, who have the least work at the beginning of the year, still rise early out of habit.

It is winter, but snow is nowhere to be seen. If on a sunny day one looks at the green magnolias, examines their fleshy shiny leaves, one might think it is spring, or perhaps summer in full swing.

On such days Enzo Fiore sits in the living room on the sofa opposite the fireplace, reads “Ravenna” or, dozing, watches the pirouettes of Filipino, whose round shell seems to float above the floor, bumping into objects and spinning around its axis.

One of those days a gray turtle-dove similar to a pigeon flew into the estate. It landed on the roof of the new house and began to coo loudly, as if calling the inhabitants of the area to announce important news. And in its voice Enzo for some reason heard the intonations of Anna.

Mother said that this bird brings heat from Calabria. Of course, mother was wrong. From Enzo’s observations, the turtle-dove brings guests to the estate. Here, before the arrival of the Russian worker, that same dove had also come, with black and gray-blue “mirror” spots on the neck. It sat on the magnolia and cooed low, muffled… “Undoubtedly, the turtle-dove brings guests to the farm,” thought Enzo. “And new life. Yes, yes, new life. That is certain.”